SMUT X BOY! SMUT X BOY! SMUT X BOY!

Q&A by Andy Kelly (Oigåll Projects) Q&A by Andy Kelly (Oigåll Projects) Q&A by Andy Kelly (Oigåll Projects) Q&A by Andy Kelly (Oigåll Projects)

How long have the 3 of you have been working together? Or is this the first time? Is it true? Is 3 a party?

D: Three is always a party! We have all worked with each other individually; assisting one another in our acquired crafts. Shooting nude isn’t for everyone and it was so beautiful of both J and Karlo to listen to my ideas and help me explore them through my photography. This will be our first show as a collective.

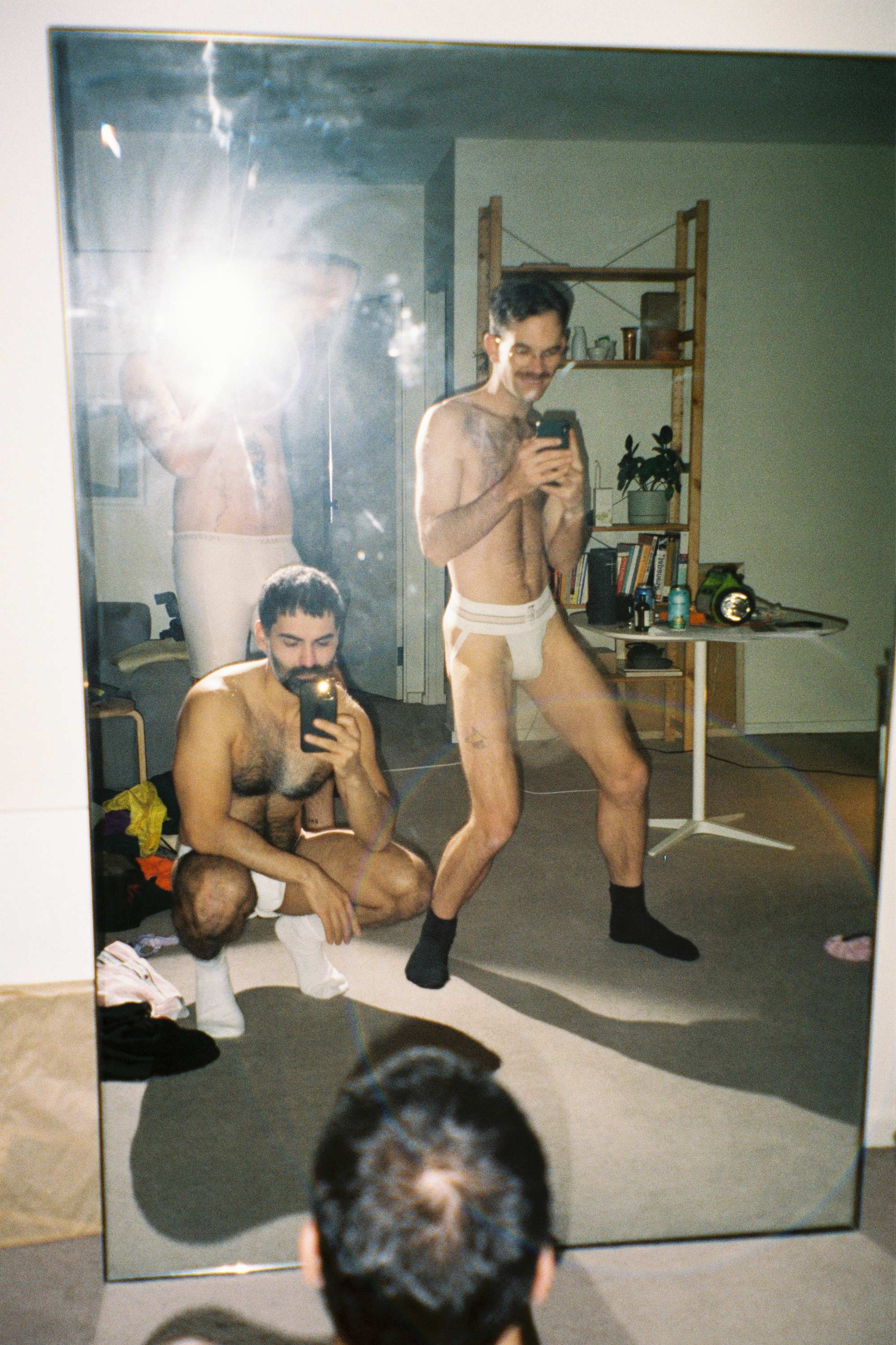

J: I think I first photographed Karlo in 2015 when I was a first-year student at the VCA, and I photographed Dylan for the first time in 2019 once I picked up my camera again. After a multitude of cross collaborations, we eventually had a night with the three of us together this past May. During this initial three-way collaboration, we dreamed up the idea of a collective where we’d create our own spaces to showcase our work freely. Now, 6 months after our initial meeting, we are only weeks away from our first exhibition, and from releasing our first issue of the SMUT Zine. I think the three of us are a party; each bringing a different set of skills and perspectives.

K: Absolutely! Three is a party. I first met Jay back in 2015 via Instagram and they photographed me for one of their projects. I then met Dylan in 2017, via Instagram as well, and we got together for some photos at a Costco parking lot–I vividly remember running around naked on an empty lot and Dylan chasing me around with his camera. At the time I was very interested in using my body to express myself via someone else’s lens or vision. I later found out Dylan and Jay had gotten in touch so naturally we all just sort of came together over the last year. I think we realised we were all exploring the same sort of subjects and themes, in our own way, and the idea of forming a collective and having an exhibition is as recent as six months ago.

What’s your opinion on queer representation in the local arts community currently?

D: From throwing myself into the Melbourne queer scene, I think I have been fortunate enough to have crossed paths with a lot of queer artists.

J: I don’t think there is much of a community effort to represent queer art or queer artists here in Naarm. I think our community represents ourselves, we fight for our own spaces and conduct our own exhibitions, performances, and parties. There is still a big divide and often that is met with tokenisation. Hopefully things will be different after our rebirth post-lockdown. Our queer community is extremely driven. We will create spaces for ourselves.

K: I think the local arts community is queer-friendly, however I do feel like there aren’t enough spaces, outside of queer-only spaces and events, that promote queer art and queer artists.

Do you find it hard to find places that want to show your work without censorship?

D: Our SMUT Exhibition with Oigåll Projects will be the first time I show any work in the physical sense. Instagram has been an incredible tool for exposure and to connect with people from around the world. Of course, Instagram has its own issues, and it has been a task navigating online censorship. However, I can attribute Instagram, and more recently Twitter, for connecting my work to people who appreciate what I do.

J: Absolutely. My work is a vast, ongoing archive of my life and incorporates a lot of different elements of contemporary queer existence. My work is driven by an insatiable curiosity, a need to relate and to understand intimacy, which means that often it can include content and themes that some people find challenging. It can be disheartening to know that my work is perceived negatively or censored because of someone else's understanding of what is 'artistic' or 'appropriate'. But I do think that often, in these cases, it is often more reflective of the viewer's own relationship to intimacy, queer or not, and the complexities and unresolved tension that they may be carrying.

K: I haven’t really approached galleries or places to show my work before this, but you don’t need to venture far to experience censorship and homophobia. Tumblr and Instagram are a prime example. Luckily, we found Oigåll Projects!

Is commerciality something any of you are worried about? Is selling work a consideration in your process or is just purely a creative endeavour?

D: I’m not too sure, commerciality is a scary thing. Like everything, it should be about maintaining integrity in your art and making sure what you are doing is not outside of what is within your comfort. I never came into photography with the thought of ever making money from it. Anything from hereon is a bonus!

J: I only recommitted to artmaking in 2019 as a way to document my life. A lot of my time that year was spent exploring and documenting my experiences with intimacy after my first real, life-changing break-up. Photography became a tool to encourage me to put myself out there more, to try new things and meet new people. Now that practice has expanded and I’m making more art than ever before! But it’s not currently sustainable. I am in the process of exploring ways in which my art practice can become financially stable.

K: I don’t think money drives any of what I do. I think the subject matter that we’re dealing with, on its own, alienates the idea of ‘commerciality.’ Unless I decide to make it big on Only Fans, of course.

Ever had any negative responses about your work? Give me a horror story.

D: No horror stories. But obviously shooting dicks all day is going to form some varying opinions. From the beginning, people have always made a bit of a pass about the content of my work. It sort of came out of nowhere in the last four years and I just went with it. I don’t do what I do for other people and have just kept at it, exploring my technique, and refining my ability. It’s been interesting seeing opinions shift from four years ago to now.

J: Absolutely. I’ve now officially had 11 Instagram accounts and countless posts reported and removed for nudity, ‘sexual solicitation’ or some other degrading sexual ‘breach’ of guidelines. I’ve had thousands of aggressive, abusive messages and comments about my work too. I’ve had people tell me “[I’m] so perverted [I] probably fuck my own Mother”. I’ve had threats made against my life; I’ve been called all kinds of terrible things.

In 2015, I ordered a stack of 6x4 prints from K-Mart to work on a new project. This was very early in my exploration of bodies and the work back then wouldn’t have had any full-frontal images. Anyway, I went to pick up my order that I had already paid for, and the person behind the counter told me they had to call their manager to speak to me. I moved to the side of a very long line of cis, white, middle-aged suburban mums and anxiously waited. Once the manager was there, I got told that my work was “inappropriate to have printed in their store” and that I was no longer allowed to use their printing facilities as it may offend someone. I politely asked if it had offended someone and if so, what about bodies was so offensive. In a very condescending tone, I was told that that wasn’t the issue. I was truthfully spoken to like a sexual predator in front of a crowd of strangers. It was really degrading and humiliating. Then earlier this year the exact same thing happened to me at Officeworks. I haven’t been back to either since.

Experiences like these really put into perspective how much shame and stigma people experience about bodies, and the comparative freeness of my relationship to them. I think it is important that people think critically about their adverse reactions to something that truly doesn’t affect them.

K: The biggest response I get when I first show friends or people that I trust what I do is overall shock and surprise. I suppose most people think that someone who does what I do would be a brazen, in-your-face, hypersexual person 24/7 and the reality is that what I put out there with my art is just a small rebellious part of me.

Who’s work inspires you?

D: Art has always been at the forefront of my life. I was deeply inspired by pop-art and artists like Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and Claes Oldenburg as a teen. I was, and still am, inspired by the conversations and controversy their art evoked at the time. Marcel Duchamp and Ai Weiwei come to mind, too. Recently, I found myself looking towards greats such as Ren Hang, Annie Leibovitz, David LaChapelle, Robert Mapplethorpe, Irving Penn, Terry Richardson, Helmut Newton, and Guy Bourdin. In saying that, I think it’s hard not to find inspiration in almost everything. I have an architecture background and attribute a lot of my design mind and inspiration to those teachings and how I immerse myself into those today.

J: Initially, early VICE Magazine. Ryan McGinley and Nan Goldin were artists I was fascinated by but never imagined I’d live a life that would be interesting enough to document in the ways that they both did. Ren Hang was another big inspiration. Synchrodogs and Wolfgang Tillmans have impacted the way I view bodies and intimacy.

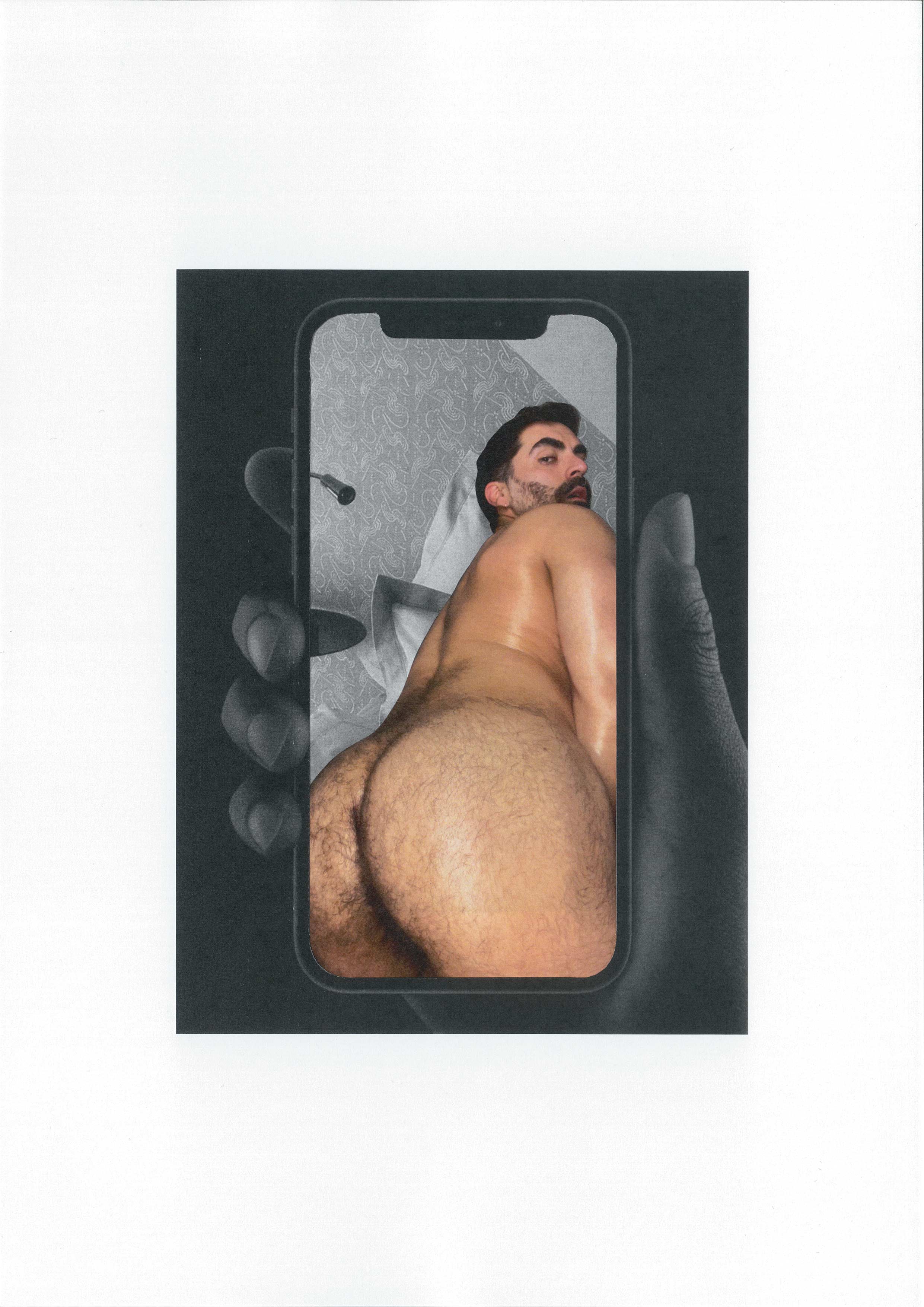

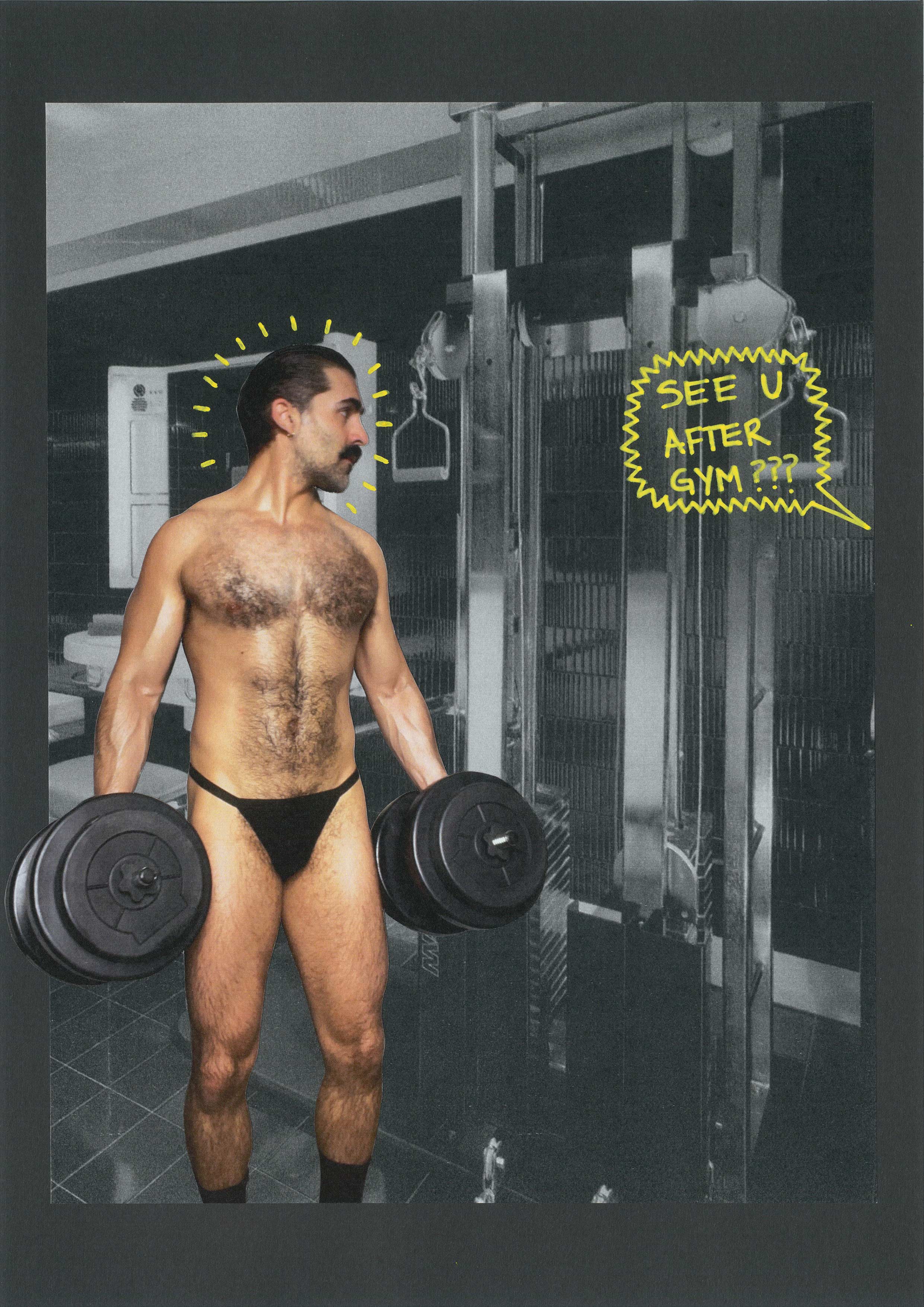

K: For my latest works, I’ve been inspired by Mapplethorpe, Haring, Hugo Comte, Brian Kenny, Madonna’s ‘Sex’ book, and Róisín Murphy’s ‘Crooked Machine’ album. A photograph, a work of art, a book, an album, or a song can inspire an idea or trigger me to create something, combined with my own sexual fantasies and encounters. Porn and overall horniness inspire me a lot too.

What is the critical process around your work?

D: Having not had any formal education in Photography or Fine Art, I think my processes are probably very unconventional.

J: My creative process varies depending on what I’m working on. I’m currently working on my first book which requires me to understand the relationships between my images, and to focus on the connection rather than the individual photographs. I often quickly lose interest in finished projects. My attention span is minimal, so I am constantly making new work to replace the old work and having new ideas I want to explore.

K: Being extremely hard on myself and a perfectionist. You have no idea how many times I’ve ‘finished’ a piece and completely torn it apart if something about it is not sitting right with me. If I look at a finished piece and something about it bothers me, even without being able to tell what exactly, I’ll know that it’s not working and to the bin it goes.

DYLAN QUESTIONS

Dylan, you grew up in Tasmania, how did you get into the business of photographing naked men?

Your little Tassie Devil! Surprisingly, Tasmania does have a few men willing to get naked in front of the camera lens. It wasn’t until I moved to Melbourne, however, that I found the freedom to start exploring my sexuality and self-expression through photography. It kind of just organically evolved into shooting nude males. I started shooting friends who supported my creativity. Karlo saw what I was doing on Instagram and was the first to put a hand up to model for me back in 2017. We shot at sunrise on top of a Costco carpark.

The subjects in your work, how do you find them, and within your photographs is it a collaborative process between your creative vision and the subject or do you have a very clear idea of the picture you are constructing before you free the shutter?

From shooting with Karlo, I found confidence in what I was doing and started getting people on Instagram hitting me up to shoot and it steam-rolled from there. My work is very much a collaborative process with my subjects. It is crucial for me that the model is always comfortable, especially shooting nude. This comes across in the final product and something I have fine-tuned over time. I never know what is going to come out of a shoot before I take out the camera, but I usually always have a cloudy idea of what I would like to create.

Your work has a very editorial/fashion feel. Is this a space you draw inspiration from? Would you ever consider doing more commercial editorial work or is the documenting of the gay experience the total focus of your practice?

Thank you! *blush*

The gay experience is at the core of what I am interested in when I photograph—it’s my life. However, I have done, and am open to, editorial photography. It is always interesting and challenging to try and inject a bit of ‘Dylan’ into something that isn’t purely directed by myself. Growing up in Tasmania, I have always found inspiration online through street style blogs like Street Peeper and Face Hunter and a lot of hours scrolling through blogger sites like Brian Boy, Leandra Medine of The Man Repeller, Shini Park of Park & Cube, and Pelayo Diaz of Kate Loves Me, just to name a few. I fell in love with the style, brand names and photography that went into each blog post—something that was very foreign to my Tasmanian sensibilities. I attribute this part of my life to being one of the many springboards which led me here today. ‘The future in not written yet’, and ‘never say never.’

J QUESTIONS

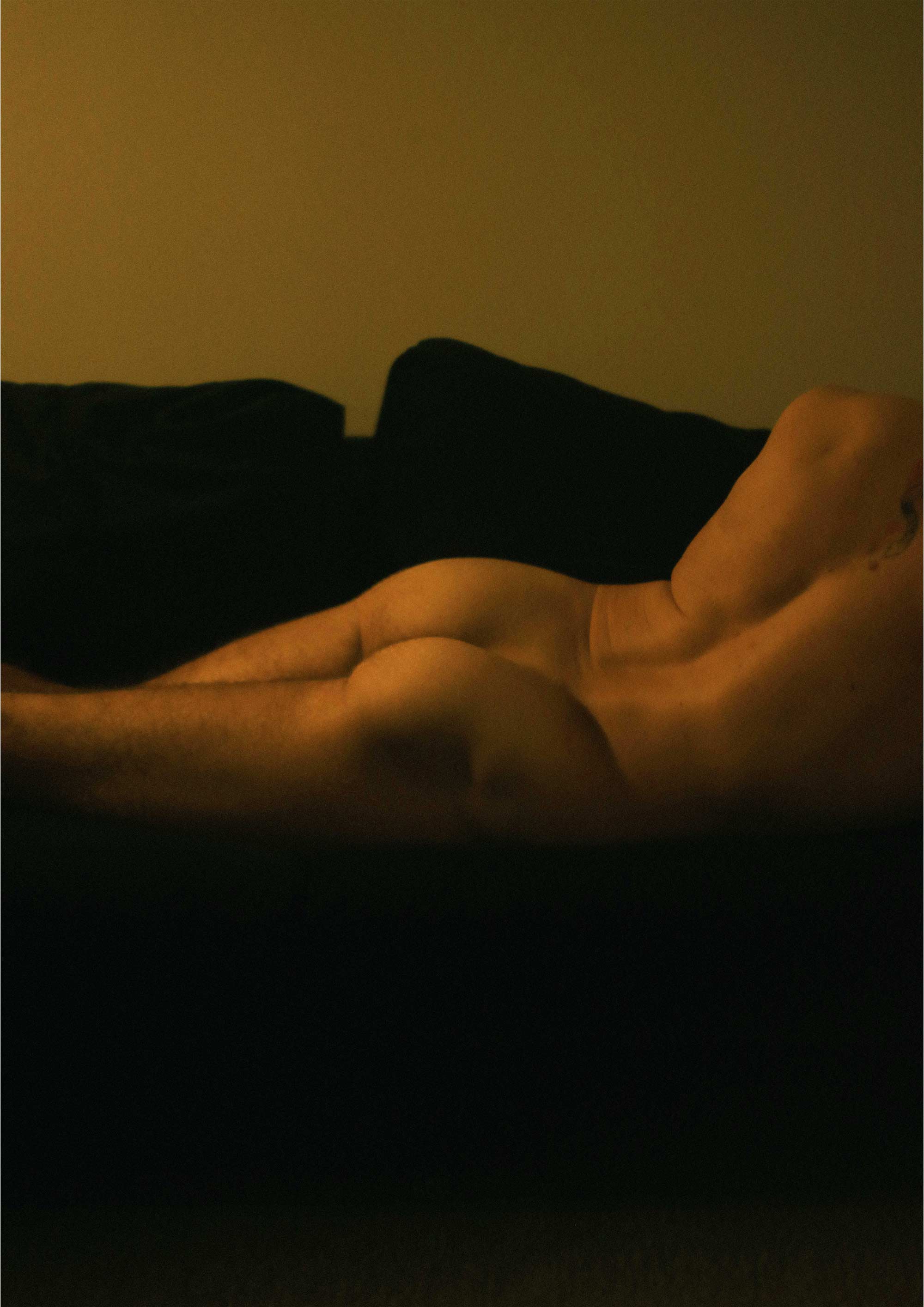

Your body of work is probably the one I find the most explicit of the cohort. Are you ever concerned about being referred to as porn over art? What do you think is more digestible within your personal sphere of Melbourne, depictions of heterosexual sex or queer sex?

What I often find most interesting about sharing my life through images is the multitude of ways in which people perceive and relate to it. I grew up shrouded in shame and insecurities. I was a bit of a late bloomer, sexually, and I explored my curiosities and questions online with other timid, curious queers. I hate that I felt so insecure about so many aspects of my life and that these insecurities prevented me from exploring. My work is, in a sense, combating that. I’m just exploring my sexuality through art, the same way that others are exploring their sexuality behind closed doors. If someone were to brand my entire art practice as pornographic, I’d be surprised at their narrow-minded perspective, but it wouldn’t change my life, my practice, or the way I feel about them. Language is completely subjective—porn is in the eye of the beholder.

My sphere here in Naarm is as queer as it could get. My friends, chosen family, my extended community here all blur the lines of sexuality and gender to the point where I forget cis-heterosexuality is the ‘norm’. I surround myself with people I feel comfortable with whether, or not, we, collectively, are digestible to the outside world. My art is a representation of this, especially for queer people who didn’t grow up with any diverse representation either.

You studied at VCA, how was your experience through that large format creative institution? Were you allowed a lot of freedom to explore the types of subject matter you do now or did your practice become more informed after you graduated?

My years at VCA were very formative. I learned a lot about myself, my art, and my own unique perspective. Initially, I really struggled, I couldn’t grasp the format of university—I didn’t understand what they wanted from me. I have a processing disorder, undiagnosed at the time, and found it extremely discouraging spending hours and hours exploring bodies with photography and having it be not well received. In my second year, I was advised to try something new—no more photography. My practice shifted to include more personal written works, mixed media, sculpture and installation, performance and occasionally painting. A change in mediums brought about a change in perspective, which I was then able to take back to photography as well.

Your work primarily focuses on human interaction and intimacy. Has this period of isolation and separation heightened this subject matter for you? The bobbing in and out of lockdowns has been to the great success of the still life artist but what has it done for a documenter of humans?

I’d be lying if I said it hadn’t been a tough 2 years for my artmaking. One positive is that my perspective on the daily monotony of lockdown changed. Over time I noticed beauty in places I hadn’t had time to notice before. I slowed down, had time to wander the streets, the back alleys, watch sunsets and occasional sunrises. I have a newfound intimate romance with the world which allowed me to continue my exploration and my work even when I couldn’t access my usual muses. I’m very excited for things to open and photograph my friends and lovers again.

DYLAN AND J QUESTION

Both of your works share a deep cinematic quality. Are you both fans of film? Have any really influenced your work?

D: Dylan e-mailed his interview answers 5 fuckin’ seconds before deadline and missed this shared question.

J: Time and the overlapping of memories and dreams influence the ways in which I document my life. I like to find areas in which an image feels like it could be the viewer's own memory, or their own dream. There’s an open-endedness, a hint of nostalgia that allows the viewer to lose themselves amongst the grain of the film. My processing disorder affects the ways in which I absorb the world around me. I lose focus very easily, but I experience a lot of stimulation through images, videos, and storytelling. I consume a lot of cinema and often find certain scenes will stick in my mind, certain monologues, actions or poses as well, whether consciously or subconsciously. When I write, it is often a stream of consciousness, intimate moments of my life, discreet details of a date, scenes from sleepovers with strangers, all compiled into nonlinear retellings. I think film and other media often weave themselves into my writings as well.

KARLO QUESTIONS

Karlo, you left Mexico to pursue your homosexuality, do you feel that you do have more freedom here to explore your practice / sexual identity by way of the social climate or was it more a personal tethering to your native home that made you feel that you needed to relocate?

A bit of both. I barely had the chance to experiment with anything gay in Mexico. I felt restrained by my family, my upbringing, my conservative hometown, and society in general. Australia seemed like the farthest place on Earth I could get to be able to fully explore the feelings and urges I had back then. Luckily, I had the excuse of studying architecture abroad. It was never about making art or artistic experimentation, that was never in my mind until recently. It was purely out of the need to discover myself first. My art practice came naturally through time and experimentation, through meeting people and fellow creatives, and even a brief stint in gay porn… but that’s another story!

Your practice incorporates several elements. Do you consider yourself a photographer or an assemblage artist? And do either of those things have more weight to you?

If I had to label myself, I would say an assemblage artist, but even then, I feel like what I do encompasses so many things. There’s photography and self-portraiture, composition, design and graphic skills that I’ve developed through studying and working in architecture, and even writing in the form of erotic short stories.

Alongside your practice, you work as an architect, is there a duality between the two different spheres of your world, or is one more escapism from the other?

Duality, for sure. I don’t consider my art practice an escape but rather a response to the repression I felt growing up and an ingrained heteronormative responsibility towards having a ‘conventional’ life and career. I’ve realised I can work in an office, have a 9 to 5 job, and be ‘professional’, but also take my clothes off and explore my sexuality openly through art. I’ve done so over the last 3 years.

MORE BOY! INCOGITO

© BOY! Incognito 2020